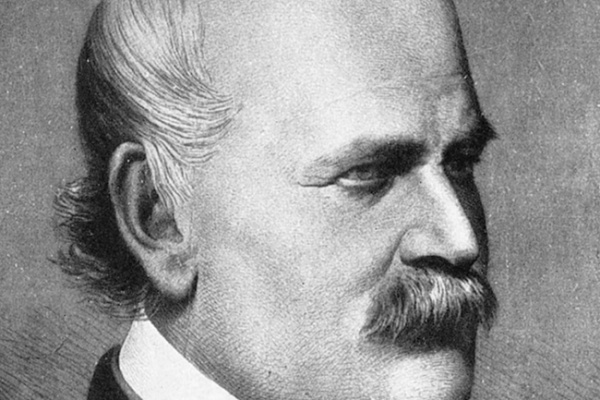

In Europe in the 1840s, many new mothers were dying from an ailment known as puerperal fever, or childbed fever. Even under the finest medical care available, women would fall ill and die shortly after giving birth. Hungarian physician Ignaz Semmelweis was intrigued by the problem and sought its origins.

Semmelweis worked in the Vienna General Hospital in Austria, which had two separate maternity wards: one staffed by male doctors and the other by female midwives. He noticed that the mortality rate from the fever was much lower when midwives delivered babies. Women under the care of doctors and medical students were dying at more than twice the rate of the midwives’ patients.

The doctor tested a number of hypotheses for the phenomenon. Semmelweiss investigated whether a woman’s body position during birth had an impact. He studied if the literal embarrassment of being examined by a male doctors was causing the fever. Perhaps, he thought, it was the priests attending to patients dying of the fever that scared the new mothers to death. Semmelweis assessed each factor and then ruled them out.

After removing these other variables, Semmelweis found the culprit: cadavers. In the mornings at the hospital, doctors observed and assisted their students with autopsies as part of their medical training. Then, in the afternoons, the physicians and students worked in the maternity ward examining patients and delivering babies. The midwives had no such contact: They only worked in their ward.

In 1847, Semmelweis implemented mandatory handwashing among the students and doctors who worked for him at the Vienna General Hospital. Rather than relying on plain soap, Semmelweiss used a chlorinated lime solution because it totally removed the smell of decay that lingered on the doctors’ hands. The staff began sanitizing themselves and their instruments. The mortality rate in the physician-run maternity ward plummeted.

In the spring of 1850, Semmelweis took the stage at the prestigious Vienna Medical Society and extolled the virtues of hand washing to a crowd of doctors. His theory flew in the face of accepted medical wisdom of the time and was rejected by the medical community, who faulted both his science and his logic. Historians believe they also rejected his theory because it blamed them for their patients’ deaths. Despite reversing the mortality rates in the maternity wards, the Vienna Hospital abandoned mandatory handwashing.

The ensuing years were difficult for Semmelweis. He left Vienna and went to Pest in Hungary where he also worked in a maternity ward. He instituted his handwashing practice there and, as in Vienna, drastically reduced the rate of maternal mortality. Yet his success at saving lives earned no acceptance of his ideas.

Semmelweis published articles on handwashing in 1858 and 1860 followed by a book a year later, but his theories were still not embraced by the establishment. His book was widely condemned by doctors with other theories for the continuing spread of childbed fever.

A few years later, Semmelweis’s health began to deteriorate. Some believe he was suffering from syphilis or Alzheimer’s disease. He was committed to a mental institution and died not long after, possibly due to sepsis caused by an infected wound on his hand.

**Source: https://www.nationalgeographic.com/history/2020/03/handwashing-once-controversial-medical-advice/

"I attended your story telling course some time back. And I've enjoyed keeping up my knowledge with your blog. You may not have realised however, that the Whole of Government is implementing Internet Seperation. Hence I'm not able to access the links to read your articles. Could I suggest including a QR code in your emails so that I can use my mobile to scan it and gain immediate access to the article? It would be most helpful"